Beginner's Luck in Quant Investing

Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan.

You only control the process, not the outcome. No matter how robust the research, it is inevitable that investment strategies will hit rough patches. There's a fair bit of beginner's luck involved as well: a good strategy that underperforms at launch is abandoned quickly, never to be revisited. Automating robust strategies and allowing them to paper-trade in perpetuity solves this.

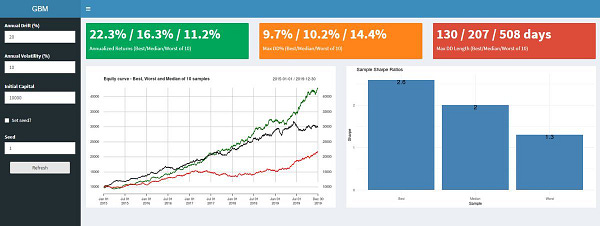

One such example is our set of Factor Momentum strategies. The theory is pretty simple: just buy whatever factor (value, quality, momentum, etc.) that worked in the previous year and hold it for one month.

Soon after we first read the research, we setup Factor Momentum portfolios for both US and Indian stocks. So far, it has worked great for US stocks but not so great for Indian stocks. We wrote up an update here.

Does this mean that the strategy “doesn’t work?” Hardly.

The “luck” factor plays a very big part in short-term investment results.

Speaking of luck, what if…

The Fama-French Value Factor premium was due to luck

We are big fans of factor investing, especially momentum. However, like everyone else, we started with value investing but quickly found out that we didn’t have the stomach for it. A few months ago, Mathias Hasler of Boston College published this:

The construction of the original HML portfolio (Fama and French, 1993) includes six seemingly innocuous decisions that could easily have been replaced with alternatives that are just as reasonable. I propose such alternatives and construct HML portfolios. In sample, the average estimate of the value premium is dramatically smaller than the original estimate of the value premium. The difference is 0.09% per month and statistically significant. Out of sample, however, this difference is statistically indistinguishable from zero. The results suggest that the original value premium estimate is upward biased because of a chance result in the original research decisions.

Back when most of these landmark research were published, data was hard to come by, difficult to store and often had to be processed by hand. Understandably, academics took shortcuts - using monthly returns, having Dec-31st as cut-offs, not discriminating between revised numbers vs. those first published, etc. While the underlying alpha might have still survived, the magnitude of it is often questionable in the present day and age where none of those data storage, management and compute problems exist.

And then, there is the famous “specification problem” in quantitative investing - the same underlying alpha can be harvested in multiple ways (different variable configurations) so each model will be (un)lucky in different time-frames.

The case against Value in three parts

The market, and by extension, is not as dumb as professional investors like you to believe. Mispricings are rare and fair-value is in the eye of the beholder (bag-holder?)

If the S&P 500 or any stock practically never is at or near fair value, the question is why bother calculating the fair value in the first place? If the Second Law applies and a market drifts towards the most likely state, it will never end up at fair value. If true, that would mean that fair value calculations are entirely useless.

Ending wealth is multiplicative, not additive. If ergodicity economics is right, then fair value models are indeed useless and misleading. And well-established investment approaches like value investing would turn out to be a historical aberration that worked for 70 years or so but did so more or less by coincidence.

People try to maximise ending wealth and not returns, they are simply refusing to enter gambles where they can lose a large amount of their wealth even if the expected return improves. And because many investors independent of their risk aversion refuse to participate in stock markets at the same time, the drop can be fast and furious.

Quite a bit to chew on this weekend!

Meme of the week

The best way to get started investing is to Get Started!